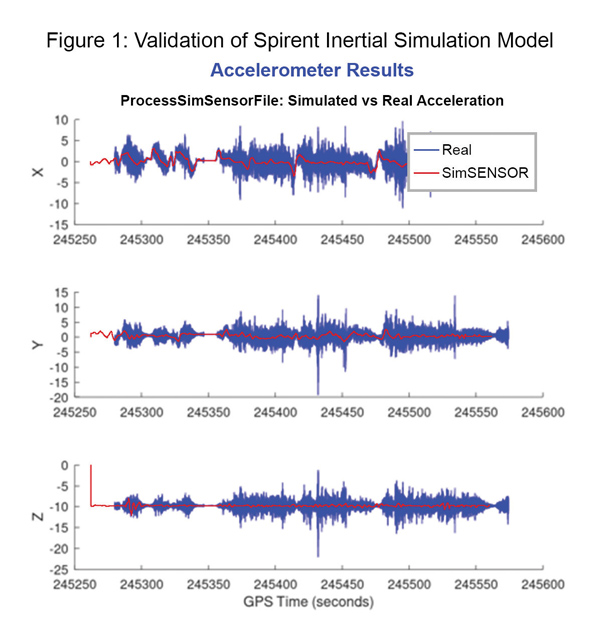

Data shows how successful baseline validation testing of Spirent’s inertial simulation model as compared to real world inertial system performance. Photo: Spirent Federal Systems

We discussed complementary PNT with Roger Hart, head of engineering and Jeff Martin, head of sales at Spirent Federal.

What are some of the most promising approaches to complementary PNT sources and how does simulation technology help?

Roger Hart: The vulnerabilities of GNSS have been recognized. Legacy GNSS are all operating on pretty much the same frequencies and power levels, so, they have some significant common vulnerabilities. There is great interest in finding ways to complement or even replace those capabilities.

Dead reckoning, magnetic and inertial systems have been around for a long time. There are emerging markets to make use of alternative radio frequencies for navigation. In some cases, we are piggybacking on communications signals and deriving PNT from them. In other cases, we are using new PNT signals. A couple that we’ve been focusing on are the alternative navigation systems.

They may be using different orbits, different frequencies, different encoding schemes that set them apart from the legacy GNSS systems, so that, used together, they provide greater resiliency and even stand alone when one or the other system may be affected by interference.

Not to be forgotten is inertial navigation. It’s been around for a long time and is still a standard of navigation. Together with GNSS, it makes it a terrific navigation system. It almost defines complementarity because where GPS is vulnerable inertial can fill in the gaps and where inertial drifts GPS does not. So, paired, they make a very strong system.

At Spirent, we’ve been working with customers to provide a variety of options for both those alternative navigation systems and inertial. Both are a very active field of development and we’re keeping abreast of that.

Jeff Martin: Some good points, Roger. This is something we’ve been engaged in for quite a long time. Since we provide test equipment to the community, it’s critical that we understand what they’re worried about, what the vulnerabilities are. It keeps things exciting, it keeps us on our toes and looking ahead to what’s coming.

What are some of the remaining challenges of integrating GNSS receivers with inertial sensors and, again, how does simulation technology help with that?

Hart: Inertial works by integrating sensor measurements that come in. Therefore, any errors that are present just accumulate over time and can corrupt your navigation solution. So, there’s a strong focus on updating error models and on translating them so that everyday users can use them and get real-life-type performance out of them.

There’s a tendency to think of integrating GPS-INS as putting everything together in one box. There are packages that do that. However, the push now is to go to more distributed systems that are integrated but not packaged in the same box. One example is the all-source positioning and navigation standard that is being developed by the Department of Defense. It will allow you to swap one sensor for another as long as they adhere to the standard. That information all goes back to a sensor fusion engine.

Martin: We have known GNSS simulators well for about four decades. We have been playing in the inertial sandbox for at least a couple of decades as well. This has given us the opportunity to build relationships with the with the key manufacturers and designers of inertial systems. Those relationships have been expanding well beyond inertial to many other sensors and systems that are now coming online. It’s been exciting.

Much work is going into using low Earth orbit satellites for PNT—whether piggybacking on the Iridium satellites or launching new ones. How does simulation help with that?

Hart: It certainly helps with the development of the receivers. The groups that are using these alternative RF and LEO or MEO systems need simulation as they develop the receivers. It gives you the ability to try things certainly before you launch them. At this conference there is considerable interest in making things reprogrammable. We have the NTS-3 satellite, which will be running experiments for different waveforms that can be generated. Even M-code is a step in the direction of giving more flexibility to the signal. It has a lot more flexible cryptography and signal generation than the legacy system with the C/A and P/Y codes.

Our simulation platforms are software based, so we can generate and receive data that can be useful for developing software-defined receivers. It gives you the opportunity to try different waveforms. We have already delivered a satellite-based alternative navigation system simulator. Now, we can build on that one to help the other Leo constellations as they come forward.

Martin: Roger put it well. This is where things get fun. People are concerned with PNT vulnerabilities, so we’re seeing these alternative navigation solutions coming forward. Spirent has done a good job over its nearly 40 years of existence of manufacturing and designing its own hardware and software. It has given us the opportunity to respond quickly. These things are coming fast. People need solutions quickly. We have some solutions already and the platform that we have created gives us the flexibility to develop more. We’re seeing more and more ideas come to fruition and people need to test them. So, this is where it gets fun. We’re excited.

Much work has gone into addressing the enduring challenge of urban canyons. How does simulation technology help?

Hart: Urban canyons are the worst nightmare for GNSS signals. If you’re surrounded by tall buildings, signals are blocked. You may have few or even no satellites in a direct line of sight and many multipath reflections. So, diminished and corrupted signals are available to you. Of course, the more GNSS satellites you have, the better chance you have of getting good signals. But complementing that are radar and vision systems. Those are the ones that will stand out, particularly the vision systems that can read the street signs, see where the curb is, look for parked cars. All those kinds of things will help fill in when you have poor GNSS coverage.

You can observe what’s going on in the environment and simulate it. You can also use our forecasting tool to look ahead.

Martin: This is where things get exciting, isn’t it? In these terrible environments where GNSS is contested—whether it’s an urban environment or one with intentional jamming—there is a lot we can do to help our industry. When this happens in real life, it’s bad news. But when you create that scary situation in the controlled environment of a laboratory, it is great. You can pick things apart and see where you need to improve. I get excited about it. It’s probably the geek in me. It gives us and our partners a lot to look forward to.

How does simulation technology help with sensor fusion?

Hart: It definitely helps you put all the pieces together. You can’t know how your system will work by individually testing each piece. System is the key word here. Simulation enables you to generate the signals and bring them together into a sensor fusion engine. You can test different algorithms. It’s certainly much cheaper and quicker than trying to build this into a product and then test it. Over the decades, simulation has proved itself as a very valuable way in both basic development and integrating the final product.

Martin: That system-wide fusion is where the magic happens.

It sounds like simulation technology—and Spirent Federal in particular—are very much at the center of a lot of the current developments and discussions about complementary PNT. Do you have any final comments?

Hart: As Jeff said, it’s an exciting time. There are many things going on—new technologies, new ways of communicating. It’s a busy time and a bit of a scramble sometimes to keep up with all the new things that are coming.

Martin: People look to Spirent to be their testing resource and it puts us right in the middle of it.