By all accounts, it is getting worse. Hundreds of internet sites sell inexpensive devices to interfere with GPS and other GNSS signals. Estimates place the number of devices extant in the United States in the tens of thousands or more. Studies show accidental interference happens about ten times more often than deliberate jamming.

In January a high-power signal in the Denver area impacted GPS reception across 4,000 square miles of airspace. The source was located, and the signal terminated after 33 hours.

October saw a similar event near Dallas that lasted for 44 hours before it ended on its own. The source of that signal was never identified.

The United States spends more than $2 billion a year to operate, maintain, and refresh GPS. Its positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) services underpin virtually every technology, every facet of the economy. Yet, as was dramatically demonstrated at least twice this year, the nation does not have the ability to quickly characterize, locate and mitigate even the most powerful jamming signals.

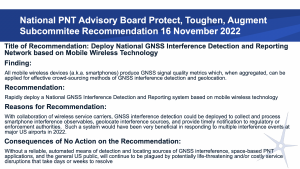

The President’s National Space-based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Advisory Board is a panel of GPS and navigation policy experts that meets twice a year to advise the government on such issues. In November, they recommended that the government establish a “National GNSS interference detection and reporting network based on mobile wireless technology.”

National Space-based PNT Advisory Board, November 2022 Image: NASA

The board made a similar recommendation in 2018 as a part of a more comprehensive discussion of actions the nation should take to protect GPS signals and users.

The group’s most recent recommendation is to implement a detection network based on crowdsourcing and smart phones. This would be done in collaboration with wireless service carriers.

Image: Page 17 gps.gov

Yet cooperation of wireless carriers, while helpful, may not be necessary, according to at least some experts.

Dr. Dennis Akos of the University of Colorado has developed an app for Android smart phones that enables devices to detect and automatically report interference with GPS and other GNSS signals. The app uses four detection methods based on location data already used by Android devices. These are comparing GNSS and network locations, checking the Android mock location flag, comparing the GNSS and Android system times, and observing the automatic gain control (AGC) and carrier-to-noise density (C/N0) signal metrics.

Akos recently presented his work at an Institute of Navigation (ION) webinar. Video of the webinar is posted on YouTube. His paper can also be downloaded for free from the ION website.

Commenting on Akos’ work, GNSS expert Logan Scott suggests that the U.S. government could use this new capability to establish the first phase of a national GPS/GNSS interference detection network with very little cost or effort.

“The US government provides managed phones to many government employees,” he said. “Having an app like Dennis’s operating on an opportunistic basis, [only when GPS is on in the phone] would give access to millions of phones as observers. Bottom line, the US could stand up a national observation network on an accelerated timeline, understand the nature of the threat, and avoid the embarrassments of [events such as those that occurred at] DIA [Denver International Airport] and DFW [Dallas Fort Worth airport]. And it would not cost much.”

If an effective system of some sort is not implemented, American lives and property will be at continued and increasing risk. In the words of the Advisory Board recommendation:

Dr. Dennis Akos. Image from University of Colorado’s website.

“Without a reliable, automated means of detecting and locating sources of GNSS interference, space-based PNT applications, and the general U.S. public, will continue to be plagued by potentially life-threatening and/or costly service disruptions that take days or weeks to resolve.”