News from the European Space Agency

Your phone or satnav receiver routinely picks up signals from navigation satellites in order to tell you precisely where you are. But have you ever thought what happens to those satnav signals afterwards? A foresighted ESA inventor had the idea of using them as a tool for observing the Earth.

More than 120 satellite navigation satellites are in orbit, making up multiple constellations including Europe’s Galileo system, sending down a continuous rain of satnav signals for the benefit of users worldwide. Just like visible light, these microwave signals go on to reflect off Earth’s land and sea surfaces.

The traditional attitude to these reflected signals is to see them as something of a nuisance — known as multipath, they can confuse satnav receivers and reduce their overall accuracy.

ESA microwave engineer Manuel Martín-Neira, inventor of the PARIS reflectometry concept. (Photo: ESA)

But back in 1993 — at the same time as the US GPS satnav system reached its full constellation of 24 satellites — a young ESA microwave engineer called Manuel Martín-Neira came up with the idea of treating these satnav reflections as a scientific resource instead.

“My head of division asked me to come up with a budget-friendly way of increasing the overall sampling rate to build up a fuller picture of mesoscale phenomena, and that led me to start looking into making use of additional signals of opportunity, chiefly satnav signals.

“The initial reaction was mixed, because the forecast accuracy was not as precise as the ERS-1 altimeter could deliver — but on the plus side there would be a lot of these signals to make use of, and the performance has improved a lot since those early days.”

Inspiration from reflection

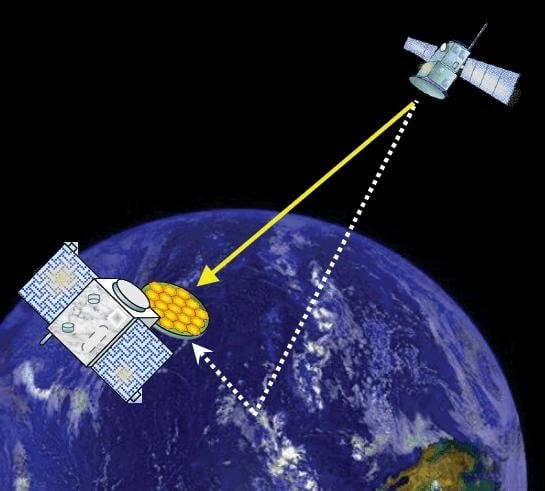

The basic idea of what Manuel christened the Passive Reflectometry and Interferometry System, or PARIS, comes down to a two-sided antenna. As the topmost side picks up a satnav signal from the satellites in orbit, the other side picks up the version of the signal bounced back from Earth.

By comparing this initial, overhead signal with its reflected equivalent using a process called interferometry — measuring tiny differences in signal phases – the extra travel time of this reflected beam can be determined, down to an accuracy of less than five centimetres, determining sea height and sea ice thickness.

Additional amplitude waveform processing can deliver further data on wind and wave measurements over the ocean, and soil moisture and biomass over land.

Satellite reflectometry has since grown into a thriving field. This summer, Manuel attended the latest international workshop on the method he first devised 26 years ago.

Reflectometry reaches space

“It’s been fantastic to have experimental evidence, and that’s really been made possible by the growing availability of smaller satellites,” explains Manuel.

“Because satellite reflectometry is a passive form of remote sensing, it makes for an attractive potential payload because it doesn’t need a lot of power to operate. Then one of the results is meteorology data that private companies intend to make money with by delivering to public agencies.”

Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd.’s UK-DMC satellite was the first orbital mission with a reflectometry payload. (Photo: ESA)

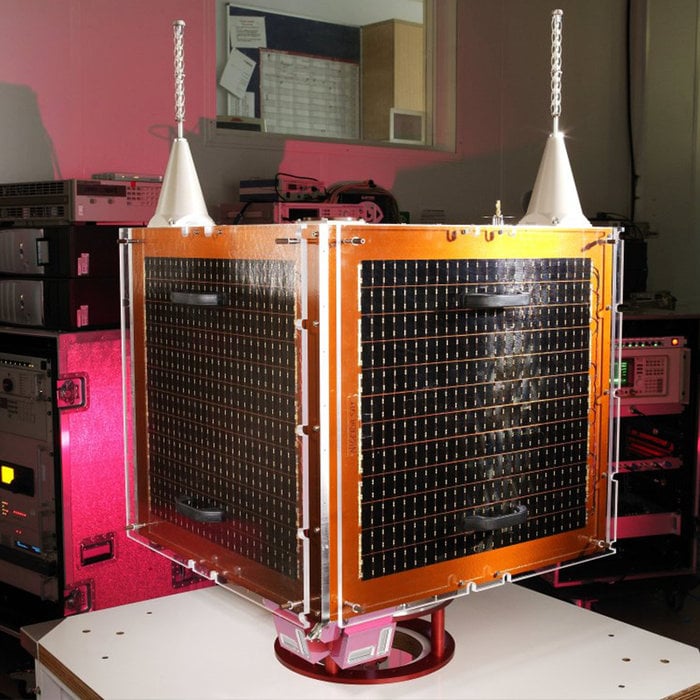

In 2003, the UK-DMC satellite was the first mission to fly a reflectometry payload, followed in recent years by, for example, the UK’s TechDemoSat-1, NASA’s CyGNSS constellation to monitor hurricanes and the Spire global constellation of commercial nanosatellites.

“These satellites have really given the reflectometry community a wealth of signals, demonstrating what reflections look like over different surfaces including sea ice, forests, and even inland water bodies such as the Amazon River and its tributaries.

“In parts of the ocean near continental masses and within atolls we are seeing reflected signals from very calm waters which resembled a mirror, giving us very high precision down to 1 cm level. Such measurements could potentially complement current altimetry missions, by for instance measuring sea level rise.”

ESA activities taking flight

ESA meanwhile is active on reflectometry in various ways, having developed and tested a steerable airborne antenna called the Software PARIS Interferometric Receiver or SPIR, capable of steering separate antenna beams to build up a rapid surface picture, and differentiating between different signal sources, such as GPS from Galileo.

Manuel adds: “ESA’s GNSS Science Support Centre, based at the Agency’s European Space Astronomy Centre near Madrid, has been taking a keen interest in these activities.”

Missions are also in development, including a dedicated CubeSat with RUAG-Austria and the University of Graz called PRETTY (for Passive REflecTomeTry and dosimetry, which would also carry a radiation detector), and a small satellite pair called FSSCat from Spain’s Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, backed through the Copernicus Masters competition, seen as a prototype for a future reflectometry constellation.

ESA’s Directorate of Telecommunications and Integrated Applications is also working with the Spire company to fly enhanced reflectometry instruments, starting at the end of this year.

One of Spire’s Satellite Manufacturing Technicians (Tomasz Chanusiak) tests the Radio Frequency capabilities of a LEMUR2 nanosatellite in Spire’s cleanroom in Glasgow, Scotland. (Photo: ESA)

When it comes to the thriving state of today’s reflectometry community, Manuel recalls the patenting of his idea as a turning point: ‘Having had this idea, which was not particularly well received, the proposal by ESA’s Patents Group to patent it made all the difference. It gave me a feeling of confidence, that somebody else at least saw the potential of this idea — and the rest is history.”